Dear all,

Here is the article from WSJ with the relevant information.

Regards

James

The Real Estate Nightmare Unfolding in Downtown St. Louis

The office district is empty, with boarded up towers, copper thieves and failing retail—even the Panera outlet shut down. The city is desperately trying to reverse the ‘doom loop.’

Many offices are empty, and shops and restaurants have closed in downtown St. Louis.

By Konrad Putzier

Follow

| Photographs by Eric Lee for The Wall Street Journal

April 9, 2024 9:00 pm ET

2258

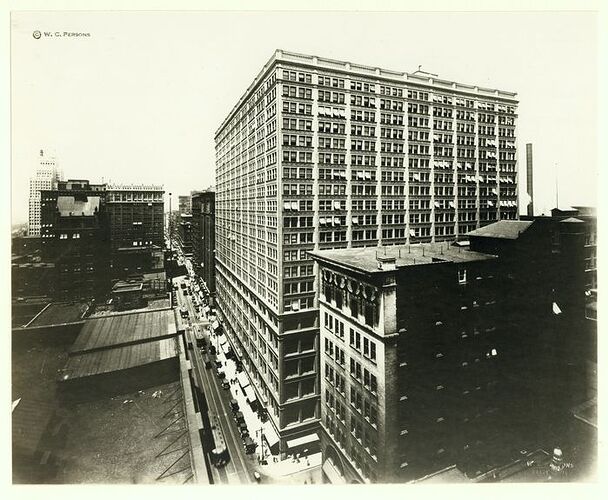

The Railway Exchange Building was the heart of downtown St. Louis for a century. Every day, locals crowded into the sprawling, ornate 21-story office building to go to work, shop at the department store that filled its lower floors or dine on the famous French onion soup at its restaurant.

Today, the building sits empty, with many of its windows boarded up. A fire broke out last year, which authorities suspect was the work of copper thieves. Police and firefighters send in occasional raids to search for missing people or to roust squatters. A search dog died during one of the raids last year when it fell through an open window.

“It’s a very dangerous place,” said Dennis Jenkerson, the St. Louis Fire Department chief.

It anchors a neighborhood with deserted sidewalks sprinkled with broken glass and tiny pieces of copper pipes left behind by scavengers. Signs suggest visitors should “park in well-lit areas.” Nearby, the city’s largest office building—the 44-story

AT&T

Tower, now empty—recently sold for around $3.5 million.

The Railway Exchange Building circa 1930, when it was in the heart of a lively downtown. PHOTO: W. C. PERSONS/MISSOURI HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Cities such as San Francisco and Chicago are trying to save their downtown office districts from spiraling into a doom loop. St. Louis is already trapped in one.

As offices sit empty, shops and restaurants close and abandoned buildings become voids that suck the life out of the streets around them. Locals often find boarded-up buildings depressing and empty sidewalks scary. So even fewer people commute downtown.

This self-reinforcing cycle accelerated in recent years as the pandemic emptied offices. St. Louis’s central business district had the steepest drop in foot traffic of 66 major North American cities between the start of the pandemic and last summer, according to the University of Toronto’s School of Cities. Traffic has improved some in the past 12 months, but at a slower rate than many Midwestern cities.

Now, it stands as a warning to others: This is the future for America’s downtowns if they can’t reinvent themselves and halt the downward spiral.

The Railway Exchange is now empty and ground-floor windows are covered with steel plates in an effort to deter thieves and squatters.

A fire broke out last year, which authorities suspected was caused by copper thieves.

On a recent Tuesday morning, few people are on the streets on a 15-block stretch that makes up much of the southern portion of the St. Louis office district. Two empty storefronts exist for each open one. The office district’s northern half is a bit more lively, but not by much. Good luck finding a clothing store. There isn’t even a McDonald’s. Violent crime is rare, but car break-ins are common.

The price for the AT&T Tower, three blocks from the Railway Exchange, was a sliver of the $205 million it sold for in 2006. Its value has been falling for years. In 2022, it changed hands for just $4 million.

Jack O’Connor, who tends bar downtown at Hayden’s Irish Pub, looks out on the Railway Exchange Building across the street. Last year the city demolished a bridge connecting the building to the parking garage across the road because people kept using it to break in to the Exchange building. After intruders kicked and sawed through the plywood covering ground-floor windows, a security firm recently installed steel plates. But people keep breaking in.

Jack O’Connor tends bar at Hayden’s Irish Pub, across from the empty Railway Exchange.

“I once saw like six teenagers with skateboards and GoPros get in there,” O’Connor said. A police officer showed up and berated the kids. “They just kind of sauntered off,” he said. “But they’ve been back.”

When the pandemic broke out in 2020 and millions of employees got used to working from home, pundits predicted the demise of big coastal cities. But office districts in New York, Miami and Boston have bounced back better than skeptics feared. The nascent boom in the artificial intelligence industry is even starting to attract some businesses back to San Francisco.

It’s the cities far from the coasts that are suffering most. Six of the 10 U.S. office districts with the steepest drop in foot traffic between 2019 and mid-2023 are in the Midwest, according to the University of Toronto.

As in other Midwestern cities, the St. Louis office district has suffered a slow demise for decades. Population loss, competition from newer offices in the suburbs and failed urban planning left behind a glut of dreary, empty buildings and wide, dangerous roads. The business district has few apartments. There are some tourists, but not enough to make up for missing office workers.

“It’s a classic chicken and egg kind of deal,” said Glenn MacDonald, a professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis’s Olin Business School. “People don’t go there because there’s nothing to do. There’s nothing to do because people don’t go there.”

The St. Louis office district’s downward spiral picked up steam when the department store—by then a

Macy’s

—shut down at the Railway Exchange Building in 2013 amid a wave of department-store closures in downtowns across the country. Not long after, offices in the building—the city’s second biggest after the AT&T Tower—emptied out.

Four years later, AT&T moved out of the building that carried its name.

Nearby shops and restaurants suddenly had fewer customers, so they closed or moved. Next came the parking garage across the street from the Railway Exchange.

“That building fell apart,” said Syeeda Aziz-Morris, owner of Pharaoh’s Donuts on the garage’s ground floor.

A parking garage across from the Railway Exchange has been condemned.

With the garage’s ceilings crumbling and propped up by makeshift poles, Pharaoh’s moved out and into a new space two blocks away in late 2019. An Indian restaurant, a convenience store, a Quiznos and a karaoke bar closed. The city condemned the garage building.

Losing a Panera

From there, desolation spread south. Across the street from the garage, a St. Louis Bread sandwich shop—part of the Panera chain—shuttered. That left the attorneys at law firm Brown & Crouppen without a lunch spot.

“It’s pathetic that a Panera was the thing holding this area together, but it really did,” said the firm’s managing partner Andy Crouppen. “It brought people from five, six blocks away, it created a little bit of activity.”

“When that left, it created a noticeable void in the area,” Crouppen said. “People started walking in another direction.”

Decay in the Heart of Downtown

Fifteen blocks in downtown St. Louis sit largely quiet as office buildings have emptied out in recent years and nearby retail stores have closed.

Brown & Crouppen closed its downtown office during the pandemic and never reopened it. The firm is now headquartered in a converted factory in a residential neighborhood in western St. Louis. Several other firms also left, and those that stayed behind now often let employees work remotely. That kicked off another wave of restaurant closures.

Standing behind the counter at Chili Mac’s Diner next door to the shuttered Panera, Charlotte Herling rattles through the names of five departed restaurants within a two-block radius. “A lot of them couldn’t hang on,” she said. The only saving grace is that less competition means the diner does fine.

“We’re blessed only because there’s no businesses left,” Herling said.

Empty streets have made the office district more dangerous. Drivers speeding on wide, mostly empty roads are a menace. In early 2023, a 17-year-old volleyball player from Tennessee lost both her legs after a car smashed into her. A barbecue joint’s smoker has a bullet hole. Local shops and restaurants pay for private security guards to walk the streets and some have installed security cameras flashing warning lights.

Pharaoh’s Donuts, now in its new space, had its windows broken twice, Aziz-Morris said. Standing in her shop in early March, she pointed outside at her graffiti-covered delivery truck. “Last week somebody drew on the window itself,” she said.

The owner of Pharaoh’s Donuts said the shop’s windows have been broken and its truck has been graffitied.

Cash for pop-up shops

In a campaign to revive its office district, the city is trying to get more people on the streets. It is adding landscaping, bike lanes and traffic barriers. Greater St. Louis Inc., a business and civic organization, pays buskers to play on street corners.

The goal “is to put more people on the street doing positive things,” said Kurt Weigle, the group’s chief downtown officer.

His organization and the St. Louis Development Corporation this month launched a program that hands out up to $50,000 to retailers that move downtown to help pay for construction work. The program also plans to hand out cash for sidewalk cafes and pop-up shops.

Discounted rents and other incentives have helped fill some empty storefronts and boosted foot traffic in cities including Minneapolis, but aren’t seen to be enough to offer true revitalization.

The city is trying to revive the area with investments including subsidies for retailers and new landscaping and bike lanes.

Reversing the doom loop spiral isn’t easy once decay has set in. To boost local businesses, the city wants to encourage developers to add hundreds of apartments by converting empty office buildings. But these projects are expensive. Rents in St. Louis are low, and high interest rates haven’t made things any easier.

When investors can’t make a residential conversion work, they often choose to wait for years until funding or a buyer materializes—a pitfall of relying on private developers to revive an office district.

Take the Chemical Building, a 128-year-old redbrick former office building a block from the Railway Exchange. Three times between 2006 and 2017 investors bought the building with plans to turn it into apartments. Each failed. One of the buyers put up a banner advertising “perfectly centered living with 1,2,3 & 4 bedroom residences starting at $170,000.”

That’s about all they did. The banner is still there today. The windows above the banner are boarded up. Others are broken or covered in graffiti. The building now has a new owner who wants to turn it into a hotel.

Multiple investors have tried and failed to redevelop the 128-year-old Chemical Building.

The Chemical Building is reflected in a window.

The Railway Exchange building’s owner, a Florida investment firm, bought the building in 2017 and announced grand plans to redevelop it into apartments and retail. The firm eventually stopped paying for security and defaulted on the mortgage. The city condemned the building last year.

A decade of rot has also made a conversion harder. Few shops and restaurants are left to attract future tenants. A 2016 water leak flooded the building’s basement. The mortgage lender still wants to get paid.

“It’s a mess. They’ve ripped through the walls trying to find copper,” said developer Amos Harris, who is eyeing a conversion of the property and was recently inside. The building is much too big, the downtown apartment market too weak and construction too expensive to convert it without subsidies, he said.

Harris is now considering a plan to redevelop the ground-floor retail space and turn only half the building above into apartments, leaving the other half vacant. But even that would cost more than $200 million, he estimated. “We’re beating our heads against the wall,” he said.

New soccer stadium

In Downtown West, fans gather ahead of a St. Louis City SC soccer match at the nearby Schlafly Tap Room.

Some cause for hope is a short walk away. To the office district’s immediate west, the Downtown West neighborhood boasts loft apartments, a new soccer stadium and a train station-turned-amusement park. These developments have revived a once-abandoned industrial area, proving that people want to be in downtown St. Louis if it’s pleasant.

To the south, a cluster of bars and restaurants around the Cardinals’ ballpark is often crowded, especially on game days. Visits to the Gateway Arch east of downtown are up. These neighborhoods show how big developments and apartment conversions can attract residents, which in turn attract bars and restaurants, slowing or even reversing the doom loop.

“Outside of that office zone, it’s never been better,” said Denis Beganovic, a military planner who lives in Downtown West.

Tourist visits to the Gateway Arch east of downtown have picked up.

The reinvention of Downtown West, full of beautiful old buildings, was made possible in part by massive investments by the Taylor family—owners of Enterprise Rent-A-Car—which spent big to build the soccer stadium and bring a Major League Soccer team to the area.

“That is becoming a huge anchor,” said Weigle, of Greater St. Louis. State and federal tax credits helped pay for the redevelopment of the former train station and adjacent land, which now includes a Ferris wheel and an aquarium, among other attractions. As more fans and visitors came to Downtown West, the area became more appealing to developers. Last year, a high-end hotel opened in a former YMCA and an old industrial building reopened as apartments.

Even within the business district, the central location has attracted a few newcomers. Quentin Eddings, a 26-year-old architectural designer, moved into a converted apartment in the office district last year. His upper-floor unit has views, the rent is reasonable, hotel bars and a sculpture garden are nearby and his office is a five-minute walk away.

“It’s a nice area to be in,” he said.

Yet that’s still a distinctly minority view. O’Connor, the bartender, said his establishment has devoted happy-hour patrons but tends to empty out by 7 p.m.

“It’s awkward pointing people to bars from here,” he said. “Like, yeah, you’re in the heart of downtown. You got six blocks to get to the next open establishment.”

Across from the Exchange Building, O’Connor said Hayden’s Irish Pub empties out after happy hour.

Write to Konrad Putzier at konrad.putzier@wsj.com