This is a topic close to my heart and I think that this is a very important discussion.

The problem of how to rank an R2G and curve-fitting has multiple layers:

- On the relationship between model designers and people who use the model

1.1) WYSIATI humans vs absolutely rational econs

When evaluating a model, humans (as opposed to educated, thoughtful but unrealistic econs) (can only) use WYSIATI = what you see is all there is. (The term is borrowed from a very good read by D. Kahneman’s - Thinking, Slow and Fast).

In case of P123 this means, that people, who are interested in models, can only look at all the factors that are provided for pre-selection. The most striking stats are probably alpha by itself, the predefined “What’s important to you?” ranks on the R2G main page and the return graph. Luckily, people now become more sensible and/or cautious in evaluating models (for example liquidity and turnover after being burnt from high turnover small cap “ultra” alpha R2Gs).

Of course, every sub is different and some do a more thoroughful analysis than others. Nevertheless, on average, I assume that a tendency of WYSIATI holds for all of us when we evaluate any model.

Without taking an extreme liberal (expect subs to be educated rational econs) or conservative (expect subs to be helpless emotional, WYSIATI humans), one solution might be to nudge people in the right direction (this time, the term is borrowed from C. Sunsein and R. Thaler’s - Nudge). It is definitely not easy to decide which direction is scientifically desirable, but I think we can for example all agree on the importance of out of sample data over in sample data (as long as there is indeed a sufficient time frame of oos data available). I think that P123 could do more, for example by providing any R2G stats (alpha, Sortino etc.) as oos data. By providing the oos return ranking feature and providing the oos advice on the R2G main page, P123 has taken steps into the right direction.

I think Tom has also summarized some fairly valid points in being cautious when evaluating R2Gs:

“But, all R2G’s for the most part, may be curve fit, but poor o-s-s performance is as or more likely that deviations in performance come from a) the use or market timing and hedging, b) the small number of holdings, c) varying start dates and random fluctuations, d) the short times since inception and e) (often) the lack of proper benchmarks are much greater source of year to year variation.” We are all on a learning curve here and will find more and more factors that we can use as pre-defined settings on how to evaluate (future) R2G performance.

1.2) Building possibly bumpy models for robustness vs. smooth equity curve designing for “marketing”

Most R2Gs are designed to have a smooth equity curve or at least deliver alpha (/Sharpe/Sortino) on a very consistent basis (which is good at first sight and often good at second sight). Any deviation from the norm can quickly be implicitly judged as a flaw in the model. However, we usually have too few information to assess whether the currently presented model truly provides a lasting edge or whether it was built “to look well” (according to the WYSIATI stats). And who could blame subs (or anyone else evaluating a model)? If in doubt, you choose the model with the smoother equity curve / higher alpha, because both models could be equally flawed (unless the designers have provided extensive explanations (Oliver among others comes to mind …) - and the subs care about these additional information). Problem is, so far we only have a limited backtesting time frame. On the other hand, strategies that have worked over centuries (such as mean reversion in terms of value investing or technical analysis) sometimes had a bumpy ride along the way.

I can also empathize with Tom’s doubt that even if models were improved for robustness in terms of number of holdings and (potentially) fewer factors etc. no one would sign up. It just doesn’t look sexy on the backtest graph and for example too many holdings look tedious and costly to trade and bumps in the equity curve are a scary thing.

Possible cures to these trade-offs include (of course) more backtesting data, refrences to tests being performed with longer time frames, disclosure of the approach of designing the model and the number of rules. Maybe the last point is rather personal - I am more skeptical of absolute buy and sell rules than of ranking systems (buy/sell rules may be more prone to disregard changing relative relationships of factors) and more skeptical of 20+ formulae ranking systems (“stylized”) than of <20 formulae ranking systems.

1.3) Disclosure vs. secrecy in model building

Once you have built a great model, how do you convince people that it is truly great?

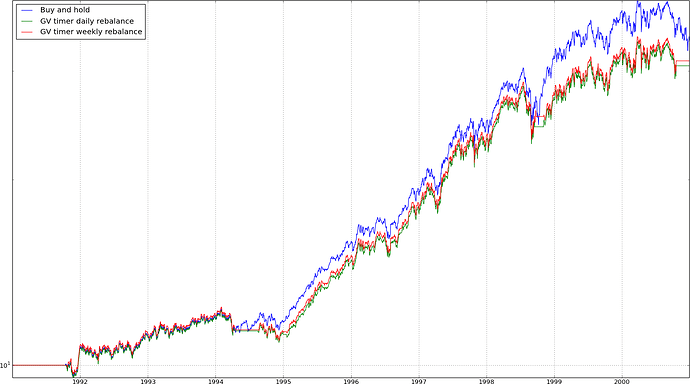

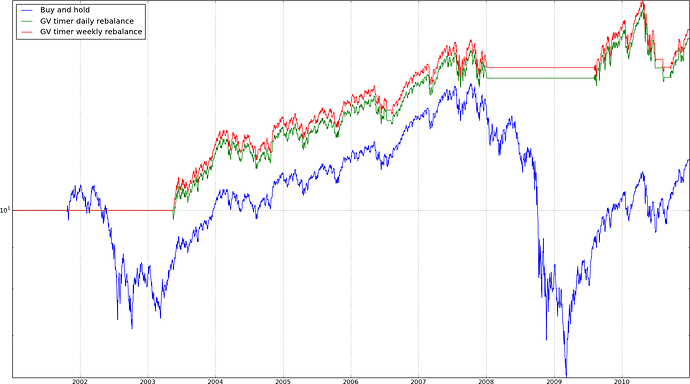

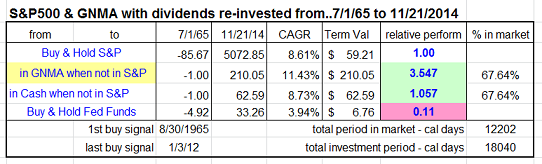

One such related, common discussion on P123 is about market timing. One can built her/his favorite model and then employ a market timing rule as a finishing touch which wipes out all the remaining dips of that specific portfolio. It looks great on the charts and stats, but does it work in the long term? On the other hand, there are many model designers on here that seem to do a very thorough analysis of their market timing models (Denny, geov among others) and can provide good reasons that these systems will work in the future. However, do they really need to disclose the exact rule they are using to convince everyone of its advantages? In the end, the designer’s ideas are proprietary and her/his valuable asset in designing models.

This sub-problem could be solved by more backtesting data, by separate (voluntary or mandatory) display of the universe, of buy/sell/market timing rules or graphs thereof (“signaling”) and by the reputation of the designer.

- On the meaning of curve fitting

I think there are different understandings of curve fitting. Some condemn curve fitting as randomly choosing factors bottom-up to produce a smooth equity curve (viewpoint a). Others argue, curve fitting is exactly what investing is about - finding factors that work, and if they do, they do so for a(ny) reason (viewpoint b - I have exaggerated these two viewpoints for the purpose of clarification).

I don’t think that these two viewpoints necessarily contradict each other. If we again take value investing as an example:

a) You condemn curve fitting by randomly trying out combinations of factors. Rather you study and reason to finally conclude that people are human and on average favor glamour stocks over cigarette butts. Top-down, you find that the price-to-book value might be a fairly sound proxy for identifying low-priced value stocks that reverse in the future.

b) You love “big data” and run tons of algos on different varieties of factors. Bottom-up, you find that the price-to-book value is an above-average predictor of future return.

Curve fitting in the bottom-up meaning is even more apparent in technical analysis. Many people argue that there is no sound theory behind technical analysis, yet professional investors run huge departments that do nothing else than valuing stocks and options by applying the principles of technical analysis. Finding a reason why this works (for example mean reversion, exaggerated fear) might be less apparent than using rigorous testing of a self-fulfilling prophecy that is more easily detected using a bottom-up approach (finding that it works simply because so many people believe in it).

So there is no good or bad curve fitting - it’s more a matter of technique and the process of building a model. It can be thoroughful either way. The model becomes more powerful if the factors can be both validated bottom-up (extensive testing) and top-down (reasoning).

Long story short - more oos data (robustness), more oos ranking factors (WYSIATI) and more rational designers and subs (by education and nudging) can improve the long-term design of models, the choice between them and the overall performance.

Best,

fips