x

[quote]

I can’t reproduce your results at all, Bob. Could you please double-check your inputs? Something odd is happening with that performance chart, which doesn’t look the least bit like mine.

[quote]

Yuval: I can’t reproduce your results at all, Bob. Could you please double-check your inputs? Something odd is happening with that performance chart, which doesn’t look the least bit like mine.

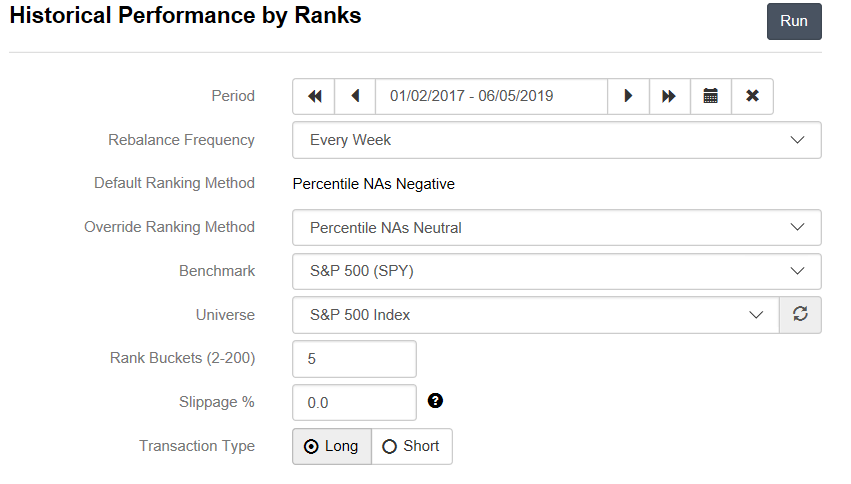

[/quote] Here’s my run setup, Yuval. Not shown: All Sectors, Minimum price $3.00, Annualized returns. There is some degradation if NAs Negative is used, but otherwise …?

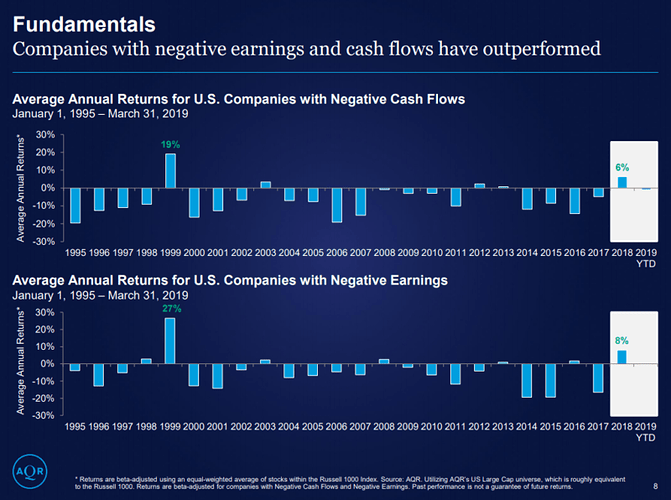

This is a value factor. But as Yuval has discuss this is also a risk factor.

That is why Piotroski has to have all of the 9 factors to make it work (to reduce the risk). I think people see risk and that is the cause for some of what is going on.

The very top buckets are always depressed for price-to-book even in markets that are not risky.

I am sure there are other or additional reasons that other members will discuss.

-Jim

[quote]

Oh, sorry, my mistake. I read 2017 as 2007. Interesting results indeed! And food for thought. It reminds me of what Benjamin Graham wrote about the P/E ratio in Security Analysis, but I don’t have that at hand.

[quote]

Yeah. Pr2Sales has been a staple of P123 ports for a long time, and was one of the keystone factors in Jim O’Shaughnessy’s What Works on Wall Street, but it’s been an underperformer for about 5 years now and it is seemingly accelerating.

Maybe we’re all just partying like it’s 1999.

That was my original question, but nobody has an answer to it. That means that factor funds are meaningless financial products.

Factor inversion is one option.

Another option—one that I am included toward—is a decay to zero. I forecast that from 2020 to 2025, the rank-return histograms of price-to-earnings, price-to-sales, and other popular metrics will be essentially flat.

Excess returns come from knowing something that others don’t, having something others don’t, executing better than others, taking risks that others are won’t, or luck. This is an exhaustive list of root causes.

I would be a little hesitant to buy any explanation that has a “this time is different” flavor as it never is. Believing a trend will continue forever is essentially that same thing.

Also, some people pull money out of the market to buy homes, education and retirement.

So who is putting that money into the market for these people? Retail investors that get out at the bottom and essentially leave money they put into the market on the table.

Or so goes some of the theories I have read.

I do not care if you like CNN, Fox, Bloomberg or whatever, they all get paid to make you emotional. It is hyped and one should prepare (in the future) to not get out at the bottom.

We focus on know what stock to buy day-to-day but not getting out at the wrong time may be more important. Maybe we need to keep more cash or whatever helps us do the right thing.

But now, hmmmm. It FEELS different so I’m not so sure.

-Jim

Common value factors are a lot more accessible than they used to be, but so are growth and quality factors. Why has value in particular been arb’ed out? You would think If anything would have been arb’ed out would be growth factors as people have been relentlessly piling into FANG stocks and QQQ for a decade.

This is why it’s so important to see factors as working together rather than as self-contained ideas.

It can never be said that a low P/E is preferable to a high P/E any more than one could say a low-end Kia is superior to a high-end Mercedes. What you pay is sensible or not relative to what you get. In stocks, the sensibility of a P/E is measured by 1/(R-G) where R is required rate of return (influenced by, among other things, business risk) and the expected future growth rate. For details, see the strategy design course.

Value cannot produce good investment returns if investors are always correct in addressing the relationship between P/E and 1/(R-G). When studies have shown that low P/E has worked over the long term, they should be interpreted to mean that over the long term, the investment community has not been effective in evaluating that relationship. Indeed, various studies have shown that the Street has a tendency to go overboard in assuming the future will resemble the past. Good growth is assumed to persist to a much higher degree than is warranted. Vice versa on the low end. Value investors make their money when reality rears its ugly head and shows investors that they were not really so wise to assume business trends would support the high P/Es they accepted for the high fliers and that they shouldn’t have been so quick to dismiss many of the market’s lesser lights.

So in truth, when you hear or read that value has worked over the long term, you should mentally translated that to read over the long term, investors have not been successful in aligning expectations to the reality that eventually unfolds. This is the condition that’s need to make value work.

What’s odd about the present is that trends (good ones for the most part) have persisted for a very long time. Really long. That means that buoyant expectations that support high P/Es have, expect in some instances here and there, not been disappointed or frustrated. Unless and until that happens, value has no room to work. If human investment community expectations continue pan out (in fact or via stories that are accepted), then value will continue to be starved of the oxygen it needs. If, on the other hand, the world develops such that investors start to lose faith in the high fliers, value will again be the place to be.

Don’t buy into rhetoric about things being arb’ed out. The most important thing . . . Not stopping at WHAT does and doesn’t work but going beyond and understanding and strategizing based on WHY things work or don’t work . . . .is probably at least a generation if not more, from coming close to being arb’ed out.

To Marc’s comment (as I interpret it) about ‘value’ operating in the space between what everyone (ie, the Market) thinks about a stock’s fair value and what a small number (or one person, ie, an analyst or a P123 user) thinks they know about that value; I wonder what the effect that Regulation Fair Disclosure (Reg FD) as well as the ubiquity of company information on the internet has had on closing this gap. Has the gap permanently disappeared (at least for larger companies)?

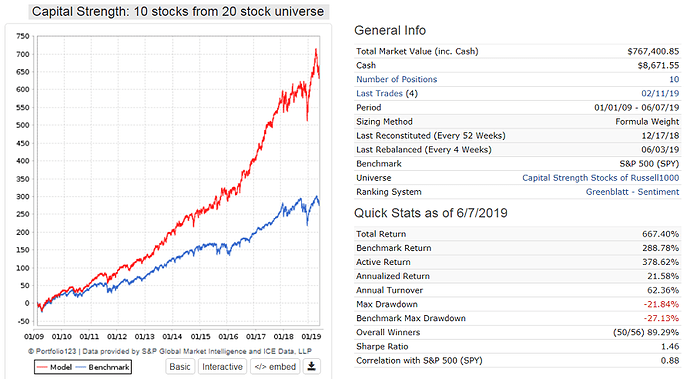

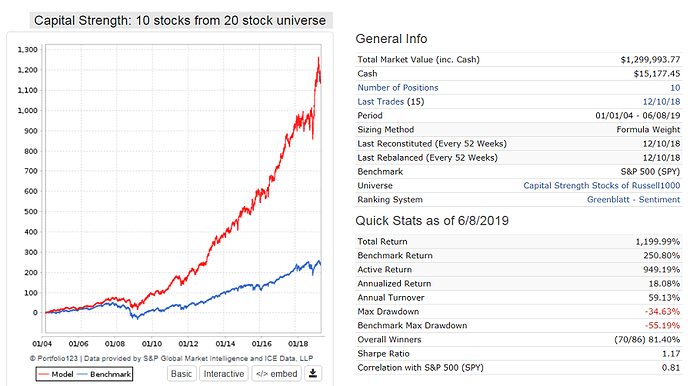

Value seems to have plenty of room to work and lots of oxygen. I am using a Capital Strength Universe. The stocks come from the Russell 1000 Index and must:

- have a minimum three-month average daily dollar Trading Volume of $10-million;

- have a Cost of Capital less than the Return on Capital;

- after meeting criteria 1 and 2, be in the top 500 securities by Market Capitalization;

- have at least $1-billion in Cash or $1.1-billion of Short Term Investments;

- have a Long Term Debt to Market-Cap ratio less than 30%;

- have a Return on Equity greater than 15%;

- have a compound annual growth rate of Earnings per Share over the last 3 years greater than 2.5%;

- and have a Short Interest Ratio of 9 days or less.

- The universe is then reduced to 20 stocks by sorting eligible companies according to the Sales percent change (recent Quarter vs Quarter 1 year ago), and Average Dividend Yield over the last 60 months.

Perhaps this is not the accepted definition of value stocks. But selecting 10 of them and reconstituting every 52 weeks, no buy or sell rules, just 1 as a sell rule, out-performs SPY every year over the upmarket period to 2019 and produced an annualized return of 21.6%. That’s good enough.

Interesting. Thank you. How did you calculate the Cost of Capital?

It’s not my invention. Credit goes to Marc who posted this some some time ago on the forum.

Interesting question, and I’m not sure the world is ready to answer it. It’s tempting to suggest that Reg FD has contributed to Mr. Market being a lot smarter than way back when Ben Graham invented him. But even beyond Reg FD, we have the overall information explosion.

But before locking in on a conclusion, I’d want to see how things look when the business cycle gets off the long trend it’s been on. It’s a lot easier for a lot more people to be right when things stay on trend for a prolonged period — people who go overboard extrapolating the past get away with it (and even get rewarded) for a longer period of time.

The more poignant question is more for economists than investors: Why have trends lengthened and are the factors likely to be sustainable? If we knew the answer to that, a lot of other issues about which we wonder would fall into place, at least somewhat.

A bit of room to work may be more accurate than plenty of room. You have your thing. My Underestimated Blue Chips DM (based on noise value), although it looked like a dog for a while, has been good lately. Mega trends aside, there’s usually room for iconoclasts to do some things. (That’s why it bothers me when I see p123 folks talking in defeatist tones. Rowboats may not be as powerful ans giant ocean liners, but they can maneuver a lot more flexibly.) But for the most part, value has been and still is suffering horrifically.

I’ve been reading a lot about value investing–Mauboussin, Graham, and others–and one thing is very clear: value investing is not about value ratios, but about identifying very mispriced stocks. As Mauboussin writes, “great investors understand the limitations of valuation approaches such as price/earnings and enterprise value/EBITDA multiples. Indeed, multiples are not valuation but a shorthand for the valuation process. No thoughtful investor ever forgets that. Shorthands are useful because they save you time, but they also come with blind spots.” And here’s Benjamin Graham, writing in the 1940s: “The whole idea of basing the value upon current earnings seems inherently absurd, since we know that the current earnings are constantly changing. And whether the multiplier should be ten or fifteen or thirty would seem at bottom a matter of purely arbitrary choice. . . . The stock market is a voting machine rather than a weighing machine. It responds to factual data not directly but only as they affect the decisions of buyers and sellers.”

Perhaps the question to ask is not why valuation ratios haven’t been working lately, but why they would have ever worked in isolation in the first place.

My own philosophy is that value ratios are useful only if combined with lots of supplementary information, sufficient to give an appraisal of a stock’s prospects and to offer solid reasons for a probable revision in investors’ estimation of its value.

My own philosophy is that value ratios are useful only if combined with lots of supplementary information, sufficient to give an appraisal of a stock’s prospects and to offer solid reasons for a probable revision in investors’ estimation of its value.

First, I think Yuval is exactly right about combining factors. We all recognize this…

Perhaps the question to ask is not why valuation ratios haven’t been working lately, but why they would have ever worked in isolation in the first place.

Yep. Marc provides one answer above. An answer a quant would give.

I looked at P123’s web site for introduction to new visitors. The word “quant” was there but it has been replaced by “FinTech.”

There is a lot of stuff going on that is very quant-like at P123. This includes heavy backtesting/optimization of hundreds of factors-if not into the 4 (5?) digits. Each factor assessed by the approved P123 techniques. There is even a little k-means cluster analysis going on there. But it is not called quantitative investing or machine learning or even behavioral investing (except by Marc).

Marc is that last of the quants at P123 —one of the people with a Financial Degree. Everyone else is a value analyst using a little FinTech.

Who would have guessed that?

I too now identify as a value analyst using a little FinTech (no degree required it seems). I find the radical ideas Marc presents interesting.

My actual point is that discussion on this forum has become almost useless. This is because the rules are that we can—at any time—identify as a value analyst and criticize almost any “radical” technique we wish.

Quant on quant in a fair fight: I am up for that. Heck, get your 4-letter-word dictionary out if you want (which no one has done but it would not bother me). I can give as good as I take. And I won’t need to insult any dead academics either. The ideas in texts used by AQR and other quant institutions (usually) and taught at academic institutions around the world do not need that (not that I am always correct in my understanding of those ideas). Indeed, I am not bothered now even with the weird rule in place: I have learned a lot in this discussion with Yuval and others. But I now fully recognize the we have virtually NO ability to direct P123 toward even a single standard practice in the area of quantitative analysis.

Look what it took to get an accepted practice that the radical quant Marc Gerstein (and Yuval himself 2 days earlier) was already using to be considered as a reasonable technique. Doing that again would get old.

I want to apologize for my sarcastic presentation of this: I was born that way. But it is also my sincere view of what the forum has become. Perhaps I can be forgiven considering I like almost every technique presented on the forum ESPECIALLY YUVAL’S. I just think we should call a foul when someone claims to be a “financial analyst” and uses that as a criticism of other’s ideas.

I won’t be going away from the forum anytime soon—unless I am pushed out. Perhaps my sarcasm (really a type of indirect proof that people do hate, I get it) will not get me pushed out today. That does not mean that I do not recognize that I should find better things to do with my time (until the rules change).

That does not mean that I don’t expect more great feature from “The Last Quant” Marc and the financial analysts at P123 either.

I do wish everyone well (not a good-bye).

-Jim

But for the most part, value has been and still is suffering horrifically.

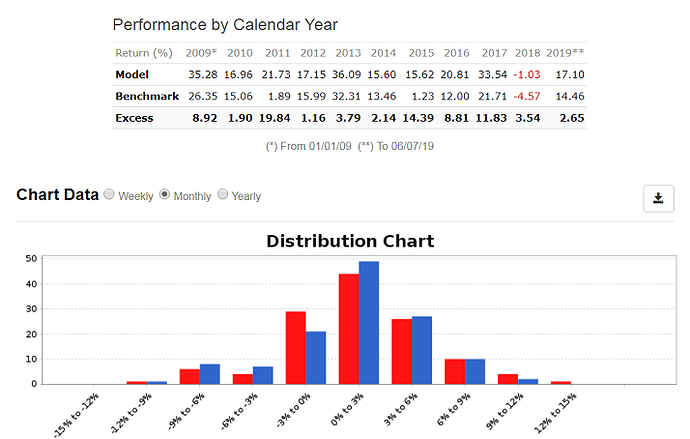

Perhaps for small-caps, but I don’t see it in the large-caps. Here is the performance from 2004. Only 76 realized trades, return=18%, max D/D=35% and Turnover 59%. It shows you that rapid trading is not necessary. Trading costs were only $9,125 with starting capital of $100,000 Check the performance spike in 2019.