I designed my first screen and it has done quite well over the decade, but during steep market declines it keeps buying, resulting in a couple of really bad years. I have seen some older threads on staying out of declining markets, but is there a buy rule that one could implement to prevent the screen from buying during signifigantly falling markets and sit in cash?

Standard disclaimer this is my own opinion and not investment advice.

That’d be the holy grail for us retail investors and probably a lot of other folks too, so I doubt there’s any easy answer. If you’re long only you COULD follow the very crude rule of turning off trading strategies if your favored index is below the 200 day SMA, but historically: 1. there are dips below it only to rally up in a mean reversion move, closing all your positions could then lose you money, and 2. if its an actual 2000 or 2008 style crash then as moving averages are lagging indicators, you typically miss the bottom and recovery rally during which there is a lot of money to be made.

I personally have looked into using volatility targeting strategies on a portfolio level, since volatility is generally negatively related to returns. In my backtested simulations (these are backtests - haven’t been battle tested.. yet) really regardless of long strategy used, adding vol targeting cuts drawdowns substantially. But, on the other hand, you do sacrifice some absolute returns since it may limit your exposure in a volatile bull market. It generally massively improves risk-adjusted returns (sharpe). You generally then need to add more money (aka leverage) to make up for the lost absolute returns in bull markets, due to the vol targeting. But, you do sleep easier with the lower drawdowns. Always tradeoffs.

Disclaimer: retail self taught investor/trader, do your own research on this, I do not pretend to be any sort of expert.

See this article I wrote a while back: Market Timing, Tactical Asset Allocation, and Trading: A Dialogue – Fieldsong Investments. Choice quote:

John Bogle said that over a 55-year period he had never met anyone who knew how to “get out of stocks at the high and jump back in at the low,” and had never even met anyone who knew someone else who could do that.

Thank you for the responses. I guess I am trying to find a way to not have a year like 2018. Every buy rule that I have tried has significantly reduced the 10 year returns.

Bogle also said that trying to beat the market is a loser’s game, no? Yet, here we are!

Timming market it s pretty difficult as far as I know...to much human behaviour involved and too many factors..maybe with AI this would change...who knows....however you can surface it for now ..there are nice threats in this forum about hedging and how to try to reduce volatility, dd without killing your soup

If we define “timing the market” as going 100% in and out of cash, then to my knowledge it doesn’t work.

However, if

- One can gradually scale out of the stock market

- Into another asset that is going up (as bonds and gold historically have done sometimes when the stock market crashes), otherwise go to cash

- Then gradually scale back into the stock market

then that’s a different ballgame.

Because the gain from missing the end of the crash + the gain from the other assets going up may be able to fully offset missing the early part of recovery.

P123 I think cannot do this. I would love if it could.

Another interesting quote is from Marian McClellan: “Everyone times the market. Some people buy when they have money, and sell when they need money, while others use methods that are more sophisticated.”

It’s interesting to me that many people fully believe they can time specific assets—entering or exiting based on momentum, conditions, or rankings—yet don’t think the aggregate market can be timed using the same principles.

To me, it’s the same underlying logic: if individual assets can display trends, relative strength, or regime shifts, then the market as a whole can also show conditions that are favorable or unfavorable for taking risk.

I’m not arguing for hyper-precision—just that broad, loose signals about overall market health can meaningfully improve outcomes. And even if they aren’t perfect, combining several different timing methods often reduces variance and smooths returns.

One of the biggest benefits is that it lets you create multiple, not-perfectly-correlated versions of the same high-conviction strategy, strengthening the overall portfolio without significantly changing the underlying model.

Market cycles create a real, measurable transfer of wealth because most retail investors unknowingly play Gambler’s Ruin.They load up near the top, panic near the bottom, and often use leverage at precisely the wrong time. Institutions—who have deeper capital pools and no need to capitulate—accumulate the shares retail is forced to sell. When markets recover, institutions earn the gains on shares that used to belong to retail.

Intelligence has nothing to do with it. Even Isaac Newton—one of history’s greatest mathematicians—fell victim to this during the South Sea Bubble, saying he could “calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of men.” Everyone must consciously avoid Gambler’s Ruin: the player with the smaller bankroll eventually loses even when the odds are fair. Add volatility, leverage, and emotional decision-making—and ruin becomes nearly inevitable.

To survive and actually compound wealth, one must avoid ruin—avoid capitulating at the bottom. It almost doesn’t matter what strategy you use; the math will never work if you get pushed out at the worst moment.

Nassim Taleb (author of The Black Swan) explains this in terms of ergodicity. In a non-ergodic system, the time-average outcome for an individual is destroyed by a single ruin event.

Without the math, his central point is that “non-ergodic” essentially means this: if you get knocked out at the bottom, compounding stops—and your long-term average becomes zero.

This reminds me a bit of the old argument that “if you miss the 10 best days,” your returns will be dramatically worse—never mind that if you missed both the 10 best and the 10 worst days, you’d historically be considerably better off overall, and that the best days typically occur in the worst markets you’d be happy to be avoiding.

I don’t like having all my eggs in one basket and tend to agree with Nassim—and perhaps even more so with Spitznagel—that the best defense against markets going down is having something asymmetric that goes up a lot during those periods.

Even so, scaling back some exposure as general market conditions deteriorate feels natural and logical to me, as just one of many risk-control levers I employ.

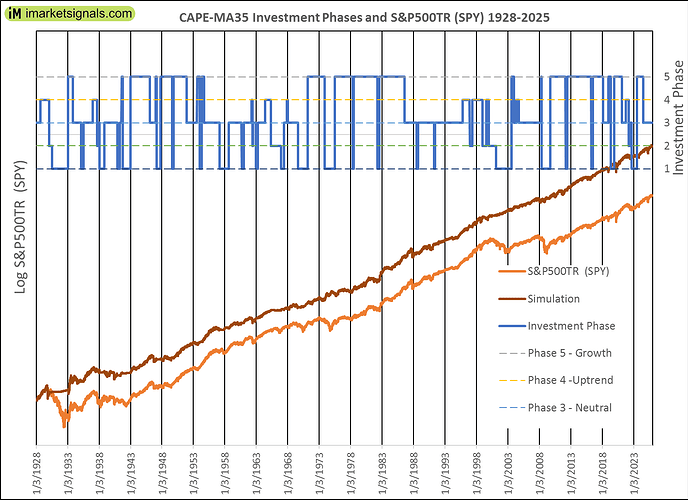

Yes, use the derivatives of the Shiller CAPE ratio.

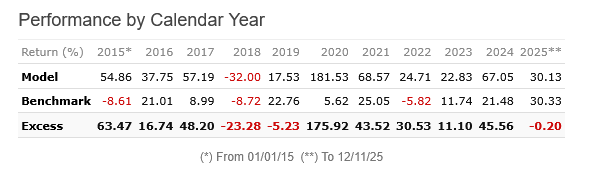

I have backtested this from 1928 to 2025. It does not work when you have a fast drawdown like the Covid crash, but it works great when you have a long declining market. The allocation , when not in the S&P, is to 50% 10-yr Treasury fund and 50% Gold. The calculations for regression slope and R2 prior to 1999 were also made on P123 using the Imported Data Series module, and setting prior dates accordingly.

| S&P500 TR Drawdown | Model Drawdown | Loss Avoidance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Depression | 9/6/1929 | 7/8/1932 | -84.14% | -31.10% | 53.04% |

| 1937 Recession | 3/10/1937 | 3/31/1938 | -52.02% | -42.01% | 10.01% |

| WWII Bear | 11/9/1938 | 4/28/1942 | -37.84% | -9.73% | 28.11% |

| 1968–1970 Bear | 11/29/1968 | 5/26/1970 | -33.00% | -12.59% | 20.41% |

| 1973–1974 Bear | 1/11/1973 | 10/3/1974 | -44.90% | 10.73% | 55.63% |

| Dot-Com Bust | 3/24/2000 | 10/9/2002 | -47.51% | 4.90% | 52.41% |

| Global Financial Crisis | 10/9/2007 | 3/9/2009 | -55.19% | 0.34% | 55.52% |

| COVID Crash | 2/19/2020 | 3/23/2020 | -33.72% | -33.72% | 0.00% |

To Georg’s point: for a crash you don’t have time to react, so you need something convex already on the books. I use deep out‑of‑the‑money, near‑term SPX puts. I always keep a big stash of them and accept that I need a higher projected CAGR from my underlying strategies to afford that carry. My belief is that they are additive over time: the occasional large payout makes up for the steady small losses. An added benefit is that the big payout tends to arrive when risk assets are at depressed prices.They also give me the confidence (and necessity) to run a more aggressive mix of strategies which helps during the good times.

To deal with long, drawn‑out bear markets (as opposed to sudden crashes), I’m looking at various timing / de‑risking methods, potentially paired with some constant exposure. As a toy example, I took a high‑returning model and then created two variants:

-

A constant 90% exposure version.

-

A random‑exposure version where leverage bounces around in such a way that the average exposure is also about 90%.

As you’d expect, both variants show slightly lower CAGR, slightly lower drawdowns, and “similar‑ish” but a bit worse risk metrics (Sharpe, etc.) relative to the original 100% exposure model. And that’s with no intelligence at all in when we de‑risk; the exposure is either constant or essentially random.

Even in that dumb case, I’d argue that having several variants of these de‑risked streams is preferable to living in just one path of the fully exposed original. You’re giving up some return, but you’re also reducing path risk and dependence on a single realization.

If we have any genuinely successful logic behind our risk‑off decisions, there’s at least some chance of getting something closer to the best of both worlds: reduced drawdowns, improved risk-adjusted returns, and still‑competitive (or even improved) aggregate returns.

The main way this experiment really hurts us is if our logic turns out to be actively detrimental—not just neutral, but consistently wrong—even after combining several different de‑risking approaches we believe in. In that case, we’d be worse off than just staying fully invested. But short of that “negative skill” scenario, the downside seems limited mostly to giving up some absolute return, with risk‑adjusted metrics often still in the same ballpark as unhedged.

A quick add: some of the recent discussion here about pairing microcap models with a 3x bear is particularly interesting to me. Beyond the strong results Charles showed, this paired variant is also negatively correlated to a tranche of ETF strategies I run. That negative correlation lets me reduce the portion of my portfolio that’s subject to my timing overlays. At the same time, I still believe those timing strategies are a separate tranche that adds value on their own, so my plan is to keep them in the mix rather than replace them.

I think part of this is a lot of smaller investors have no real risk management plans in place so they panic sell at some emotional point, instead of having predetermined plans for when to reduce exposure and when to eliminate it entirely. From what I’ve read, proper risk management often turns out to be just as important as the strategy used.

While I was still working at my day job before, we use to have a daily VaR (value at risk) and weekly VaR to measure and control the market risk of the portfolio. If there is a limit breach that is set by the market risk department, we need to deleverage and sell down some of the existing portfolio.

There is also a max loss% that cannot be breached. First you get a warning when half the max loss% is reached and there will be a cut in capital allocated. When the max loss % is breached again, there is a time-out and the whole team may be dismissed (losing your job).

Regards

James

this sounds like MLP!

NOT having this sort of logic was the hardest gap for me to reconcile when moving from discretionary trading to tactical systems. It’s what drove my obsession with layering risk protection in a way that doesn’t dilute returns—and can even improve them.

I'm afraid I don't see the difference in terms of difficulty of execution. Going to cash and going partially to another asset class should be equally successful or unsuccessful. The best way to avoid drawdowns is to have a fixed (and regularly rebalanced) allocation to an asset class that is negatively correlated with your main strategy (shorts, puts, etc.). The rebalancing will infuse your long strategy with extra cash during drawdowns, and you'll be buying low and selling high. Trying to time your allocation will get you into hot water. I know a hedge-fund manager (a P123 subscriber) who balances his long book with a short book, and he has been in the business quite a while. For some time he was using market timing to increase or decrease the short side of his portfolio. He gave that up, realizing that it was a fool's errand. The only exception now is that he intends to decrease his short positions during post-bear rallies. But there were several rallies in 2008 that really looked post-bear, so even that is a flawed idea.

Good advice for surviving market crashes:

Isn't it datamining to use a 35-year moving average? Why not a 25-year or a 50-year or a 43.5-year or a 17.87-year?

Another question: your website iMarketSignals has been coming up with market timing/tactical allocation strategies for about twelve or fifteen years, right? How many have worked well out-of-sample? And how many have worked poorly out-of-sample? Do you have examples of each?

Yuval,

I agree on the point flawed idea. Do you have any idea the size of the hedge fund managed by this P123 subscriber? Based on my understanding, how market risk is managed depends on the type of hedge fund and the size of the hedge fund (for instance, there is a huge difference between running a USD 300 mio arbitrage book and USD 3 billion long-only book (even a difference before or after leveraged). For the larger multistrategy hedge funds, the risk guidelines are set by the risk committee and manage by the risk dept. (sadly you don’t get to choose how you want to manage it.)

Regards

James

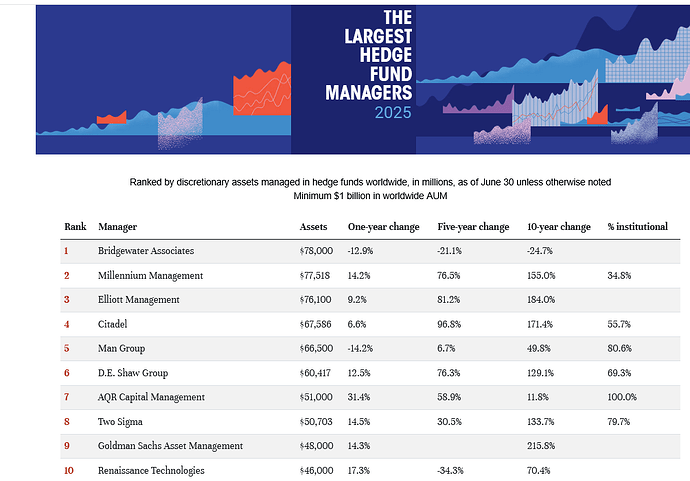

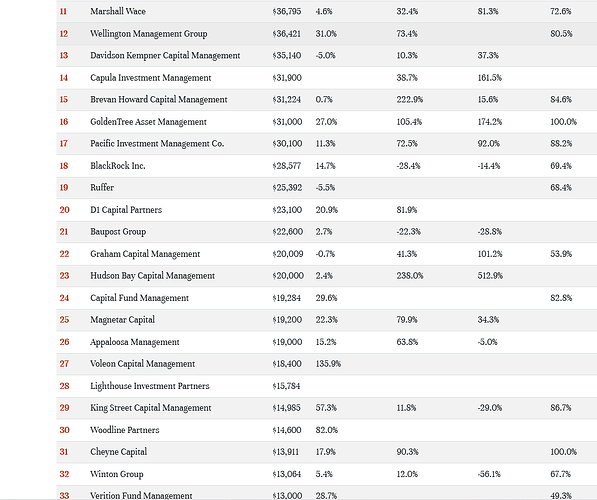

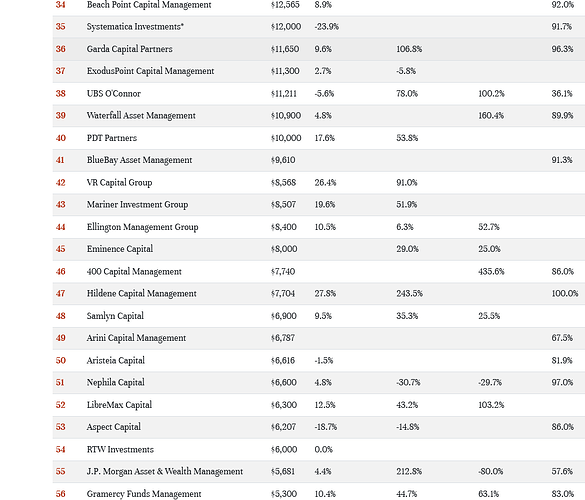

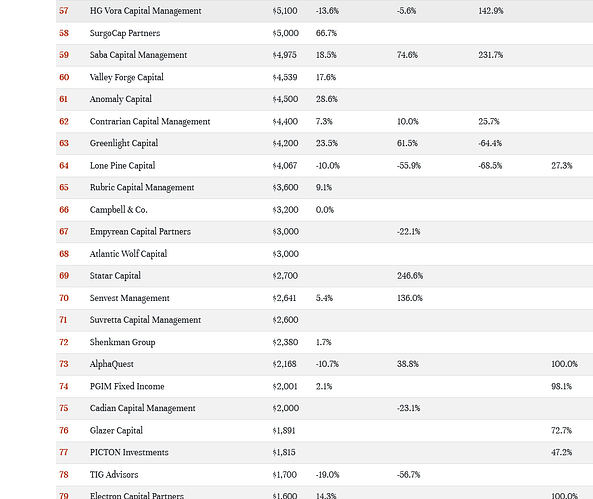

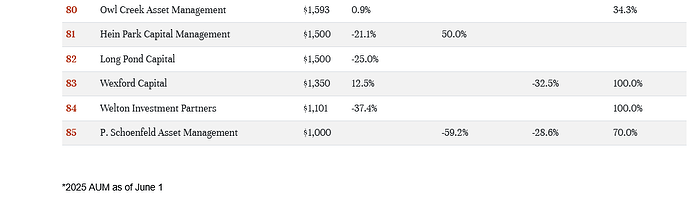

EDIT : Here is a list of the largest hedge funds by P&I. (There is a more than 50 times difference in AUM even among hedge funds with AUM above USD 1 billion.)