Hi Primus,

That’s an interesting way to calc mean reversion. I don’t normally look at companies as small/illiquid as the nanocap universe you look at (and I usually put liquidity constraints on my universes of 150k or 200k when doing studies). Slippage and difficulty trading is my primary concern. Working with a little bit larger small cap universe w/ 3-6 mo holding periods here’s some thoughts though:

I’ve added some mean reversion terms to some of my longer term models that often incorporate a lot of traditional factors, and can sometimes see an advantage/sometimes not, but there seems to be a volatility tradeoff of adding mean reversion. Over the past week or so I was looking at adding some technical rules to an existing system I’ve been using on a universe w/ dynamic market cap of 1B scaled for the value of the market going back in time (so the cap limit is lower in 2009 than it is in 2016) trying to take advantage of the technical wobbles, and in almost all cases I created higher volatility. Sometimes the sharpe might be a tad higher, but sometimes not. I was looking at 3 and 6 month holding periods and shorter holding periods will usually perform better, but I have real concerns about slippage and the slippage assumptions make much of the difference. I’m not a good trader, esp in cases of the smaller companies w/ bigger spreads, so I try to limit my chances to make mistakes there. I’m not saying anything new with this, but mean reversion probably becomes more valuable if you can trade frequently with low slippage.

I have not found quality to be of much benefit in my small cap models. I was really introduced to quant investing by Greenblatt type thinking which had quality as central fixture, but the more I look at quality factors - the less I find myself using them. Other factors seem more productive. There’s an academic word for it, I can’t recall - something like engulfs or supplants - that’s not the word - but I think maybe quality gets engulfed by other factors we can utilize in p123. (edit: maybe the word is subsumed?) If I had to make a call I’d say it’s useful for avoidance (avoid terrible quality), but not so sure it’s helpful for positive selection - at least in the way we use quality for sorting on p123.

I have not found momentum to be of much benefit in small cap models, but that could be a temporary phenomenon given history of the factor. I do not use it presently (again I’m using 3-6 month holding period targets).

Beyond that, I’ve found the kitchen sink approach has value with the smaller companies.

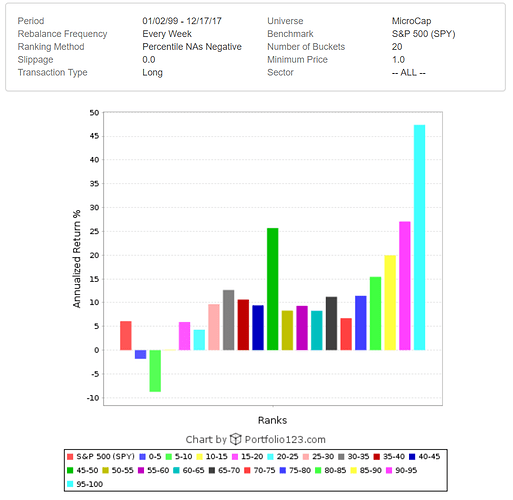

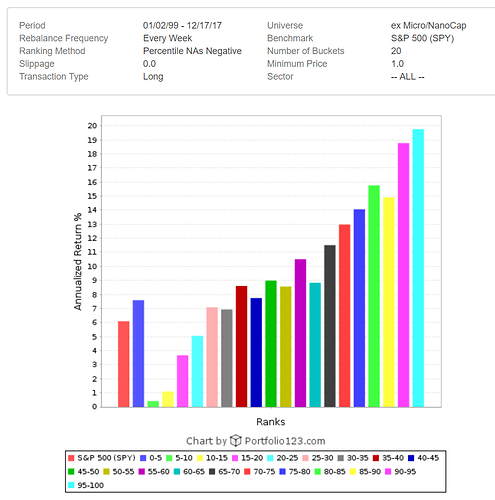

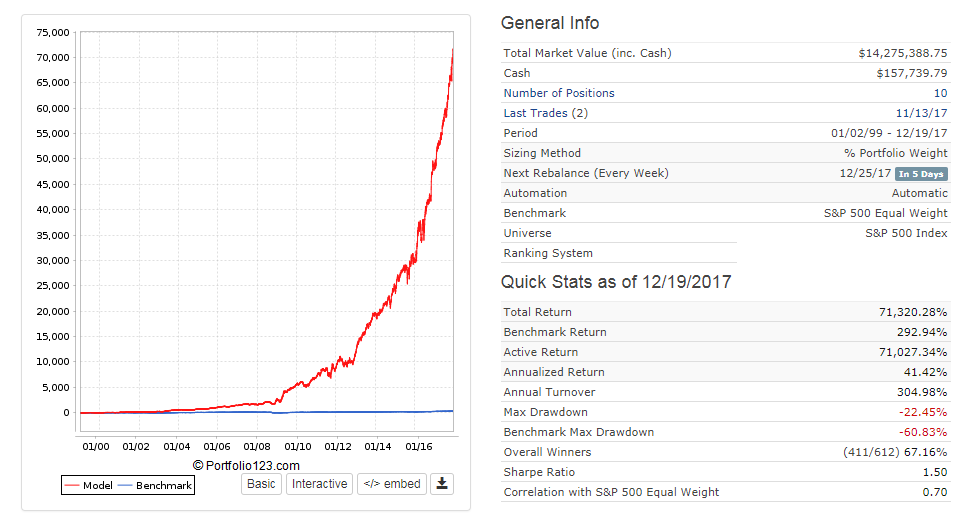

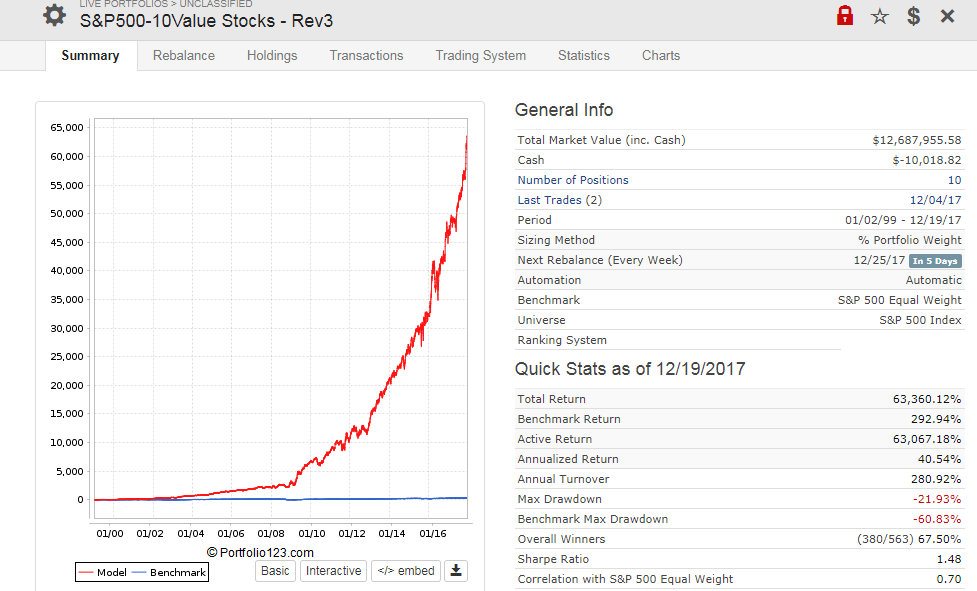

Things that work in the small companies might have little value when applied to the larger companies, or at least may not appear as easily when looking at larger companies. If I run my small cap model on the SP500 it does outperform RSP (it surprised me when it did), but the individual factors would not be apparent if starting from scratch on the SP500 and trying to figure out what works. In combination the factors do outperform and I found this result comforting. Again, this surprised me when I checked, because when researching I did not see much benefit of some of the individual factors selected when applied to larger companies - but easily saw larger performance spreads when applied to small cap universe. Performance improves going from SP500, R1000, R2000, and on down into increasingly smaller cap limitations. With the larger caps I remind myself that a small guy like me can trade more frequently with very low slippage, so I can increase frequency on the model and improved performance with big companies, so might be an opportunity there doing a retrofit.

I guess one thing to watch for in small caps are the “hump” shaped performance distributions that I think lead me to conclude that we should try to favor factors emphasizing operational stability vs. extremes of the distributions which seem mispriced. Even though there’s the idea that small caps are the land of fast growing dynamic companies, I think maybe relative stability is to be preferred in the small cap universe. Big operational changes are not a good thing, and it shouldn’t be looked at as a land of moonshots. They’re just smaller companies. Any efforts I’ve made to build models made on a high grower universe has just been sad in comparison.

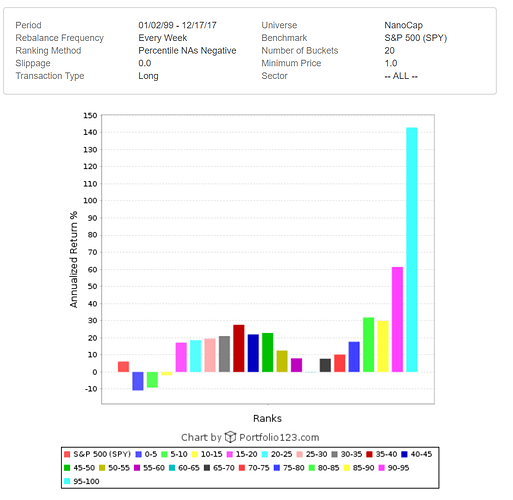

Also, there are a ton of just really trashy companies in the small cap world also. It’s probably safe to restrict your universe quite a bit at the outset if you like. I’ve done a bit of work on what to avoid, and I think probably 25-40% of small caps are likely excludable. The ranking method will generally sort them to the bottom anyway, but it’s pretty easy to build absolutely terrible portfolios in the small cap space (performance spread from best to worst expands as cap sizes decrease)

I was listening to a podcast w/ Eric Cinnamond today and he says in small caps he also looks for companies able to manage their debt payments out of operational cash flow in a 3-5 time horizon because small caps don’t have same access to credit as bigger companies. This might be a core difference. I wouldn’t be surprised to find high debt to be less of an issue in big companies. I was not able to work this type of balance sheet factor into my model when I was first building it. Debt levels were difficult for me to find meaningful factor(s) that was additive. So, I have not been able to find factors to represent this viewpoint, but he’s an expert and there’s probably something there. I’m just wasn’t smart enough to incorporate it initially, but will take another look.

While none of this is canonical, I hope some of it is helpful. You’ve probably worked on this stuff far more than I have, but I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say the kitchen sink approach seems to apply to the small cap world as I’ve looked at it, and individual factors that may not seem to have utility when looking only at large caps seem to become more useful moving down the cap scale.