Jim,

Bridgewater remains the hedge fund with the largest AUM because other large players like Citadel and Millennium has closed to new money and constantly return profit(cash) to investors to keep performance above a certain threshold.

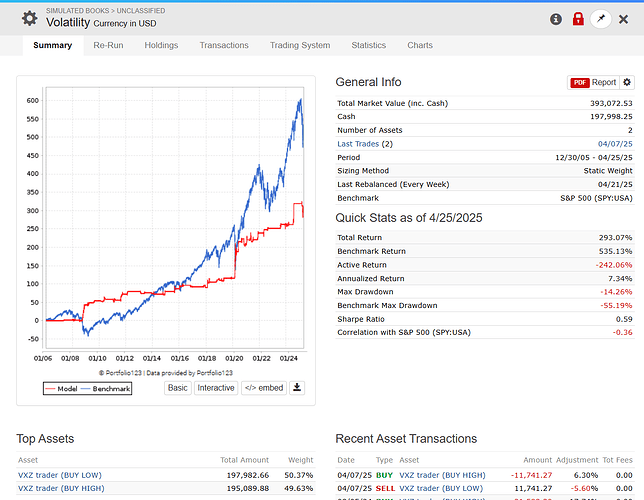

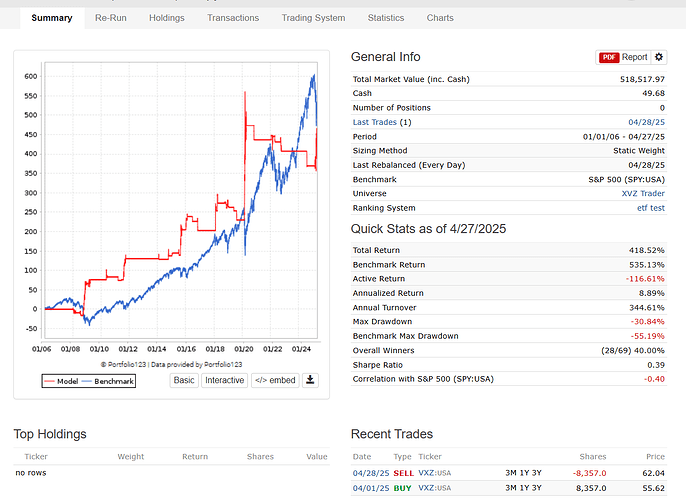

I think we have both discovered that risk parity is not really profitable before (throught the ETFs).

Pls refer to the article below about risk parity from CAIA. (equivalent of CFA in hedge fund).

Regards

James

The Unsurprising Failure of the Largest Hedge Fund in the World

August 9, 2024

sefa ozel-iStockPhoto

By Michael Edesess, Ph.D., Managing Partner / Special Advisor at M1K LLC.

Few practices in the business world are as absurd, senseless, irrational, and cynical as the allocation of investments of large public pension funds and endowments. And few fail so often and so predictably to achieve their true objectives. Yet almost all outside the industry – and many inside it – are fooled into believing the opposite. As an example, let us consider the recent news of the disappointing investment performance of Bridgewater Associates.

In late April, news reports appeared of clients’ dissatisfaction with the poor investment performance of the largest hedge fund in the world, Bridgewater Associates. Bridgewater, with $97 billion of assets as of June 2023, made its founder and chief investment officer Ray Dalio a famous multi-billionaire.

Most people assume he is a savvy investor who produces high investment returns for his exclusive institutional clients. (Bridgewater generally requires clients to have a minimum of $7.5 billion of investable assets.) And they assume that those clients, being “financially sophisticated,” must achieve high returns in the funds they invest in.

But that is not the case.

Bloomberg news reported on April 23:

It was an irresistible pitch. Give us your money, executives at Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates and other hedge funds said, and we’ll funnel it into a money-minting, sure-thing strategy for the long haul. But now, after five years of sub-par returns, many of the institutional investors who sunk large sums into risk-parity funds, as they’re known, are demanding the money back.

Bridgewater’s much-touted All Weather fund uses the risk-parity strategy, as do many other hedge funds.

How bad was that performance?

Let’s put some actual numbers on their abysmal performance. “Sub-par returns” is an understatement.

Risk parity was supposed to perform better than a 60/40 stock-bond mix. The benchmark it is compared to is a combination of 60 percent in the MSCI ACWI IMI index (global equities) and 40 percent in the Bloomberg Global Aggregate index (global bonds).

Bridgewater and the other hedge funds that practice risk parity, according to Hedge Fund Research (HFR), had appallingly bad investment performance relative to that benchmark. The numbers in the Bloomberg article show that for the 10 years 2014-2023, an investment in a simple 60/40 portfolio would have enjoyed more than twice the gains of an investment in a risk-parity portfolio. The 10-year return on Bridgewater’s All Weather fund was 43 percent and the 10-year return on the average risk-parity fund was 42 percent. Meanwhile, the 10-year return on a 60/40 portfolio was 90 percent.

This makes a very big difference to a large institutional fund, such as a multi-billion-dollar public pension fund or endowment fund. The difference between a 90 percent return and a 43 percent return can be hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars.

And yet, myriad papers – not only those published by the hedge funds themselves, but those published by academics in finance departments at universities – touted the benefits of risk parity. I will soon examine what those benefits were supposed to be. But first, let us explore the motivation behind those claims.

Principal-agent theory

In the field of economics there is a theory called principal-agent theory. Investopedia defines the principal-agent problem in this way: “The principal-agent problem is a conflict in priorities between a person or group and the representative authorized to act on their behalf.”

The problem arises because the self-interest of the agent – the person or group authorized to act on the principal’s behalf – may be different from the self-interest of the principal, the person or group who authorizes the agent to act on their behalf.

For example, a principal (the shareholders of a company) authorizes an agent (the management of the company) to act on the principal’s behalf. The implied agreement is that the agent is authorized to act only in the interest of the principal. But the agent also has their own interest at heart. That interest may conflict with the interest of the principal.

This can become a serious problem when there is substantial asymmetric information; the agent has more information about the workings of the endeavor than the principal. The agent can manipulate that information in such a way as to keep the principal unaware of exactly what is going on. The agent can do so in such a way as to direct profit to the agent rather than to the principal.

The agent can even create asymmetric information by adding a layer of complication to reports to the principal. This layer of complication can be legitimized through the formation of a society of agents of a particular type – a society of, say, chief financial officers – who create their own jargon and their own methodologies that are opaque to their principals. The agents therefore need to explain it to their principals, but their explanations may still be confusing. However, because the jargon and methodologies the agents use are legitimized by their respected society, the principals are forced to accept them.

It would be risky for the agent to be evaluated by the principal on the basis of bottom-line results of which they may not have complete control. Therefore, the agent creates a different and more arcane set of metrics on which to be evaluated – metrics that are certified by the society of similar agents, who may meet at conferences to converse in their jargon, and write papers in that jargon in peer-reviewed journals (papers reviewed by peers who are in the same society).

Principal-agent theory and institutional investors

The investment of institutional funds like pension and endowment funds is a perfect setup for enabling the principal-agent conflict. However, the institutionalization of the society of agents is so tight, so well developed and de facto legitimized, and the principals are so distant, that the agents continue to get away with bleeding the principals.

Who are the agents? They are, essentially, a conspiracy of fund administrators, institutional investment consultants, fund managers, and finance academics (many of whom are themselves, in the role of consultants, on the payrolls of the consulting or investment management organizations) – all of whom are very highly compensated out of the corpus of the funds they are supposed to manage.

Who exactly, are the principals? In the case of public pension funds it may not be perfectly clear who “owns” them, but it is clear whose cash inflows fill the funds. It is the US taxpayer whose cash inflows fill them. Public pension funds are created to fund the retirement benefits of government employees. Those public employees’ salaries, and their pensions, are funded by the US taxpayer. And yet, how many taxpayers are aware that they are paying, on average, $500 a year in taxes just to pay the managers of those funds, the managers whose investment returns, like Bridgewater’s and other risk-parity managers, underperform the simplest possible investment strategy, namely investing in an index fund.

In the case of university endowment funds, again, “ownership” may not be perfectly clear, but they are funded mainly by the contributions of donors, as well as by tuitions and grants. And yet, there has been only one instance of a major donor suing a university for its endowment fund’s poor performance, poor performance that the donor had explicitly and repeatedly warned would occur if the endowment fund kept pursuing its high-cost strategy.

Fund trustees should put a stop to this theft, but they are confounded and hoodwinked by the jargon and opaque methodologies and the fact that proposed strategies, like risk parity, are the subject of peer-reviewed academic papers and conferences – and frankly, trustees themselves are paid handsomely out of the same funds, thus benefitting from this conspiracy.

Because the principals – the contributors to the funds – are so blasé about it, the agents can, in effect, get away with murder; or rather, in this case, with making off like a bandit with a substantial portion of the funds.

Many of these agents – the investment management companies and the institutional investment consultants – like to say, not without a certain smugness, that the investment strategies they recommend are “evidence based.” However, the evidence overwhelmingly shows that nothing undermines investment performance as much as the fees paid to money managers, consultants, and fund administrators. The evidence very clearly shows that minimizing those fees should be the number one goal of the fund’s investment strategy. Yet pension funds and endowments are doing the very opposite; they are virtually maximizing fees.

High fees are the main reason the Bridgewater fund and the other hedge funds using a risk-parity strategy performed so badly. Their underperformance relative to the 60/40 index portfolio amounted to about three percent annually. Of that three percent about two percent went to fees and other compensation. A 60/40 index portfolio by contrast could have been had for one-hundredth of those costs.

What was the vaunted strategy supposed to do?

I said that in the principal-agent situation, the agent doesn’t want to be evaluated on their bottom-line results, because they may have too little control over those results. As such, it would be very risky to be evaluated on them. The agent creates other metrics on which they claim it is more important to be evaluated.

For investment management, the bottom-line result over which the agent has little or no control is investment return. In the case of the risk-parity strategy, the concocted metric is diversification. In the original development of modern portfolio theory by Harry Markowitz, increased diversification lowers risk. But the diversification of the risk-parity promoters is not Markowitz’s diversification. It is something else. It is not clear exactly what it is because it is never clearly defined. Nor is it clear why it would lower risk – and in particular, it is not at all clear why it would increase investment return, which is, after all, the investor’s bottom line.

The risk-parity argument says that in a 60/40 stock-bond portfolio the stock portion bears most of the risk, much more than 60 percent of it, because stocks’ returns vary more widely than bonds’. Therefore, the argument goes, to spread the portfolio’s risk “budget” more evenly across asset classes, the portfolio should contain much more bonds than stocks, enough more so that the variabilities of the stock portion and the bond portion are the same. This can be done without reducing expected return by leveraging, i.e. borrowing to invest more in bonds. An increased allocation to bonds will do well when interest rates are falling (such as the historical period over which the risk parity study was done) but poorly when interest rates are rising; an “All Weather” strategy it is not.

Why it should benefit the investor’s bottom line in the long run is not made clear. But a certain stamp of approval was placed on it by the society of investment management professionals because papers were written about it and conferences held. And, of course, there was – there always is – a study showing that historically, a risk-parity portfolio would have outperformed a 60/40 portfolio. But other papers claimed that the methodology of that study was flawed. And there is, in fact, considerable reason to believe that virtually all linear regression-based studies in the investment finance field are wrong.1

Conclusion

The way the investment of institutional fund portfolios is practiced is not in any sense illegal, but it is nonetheless spectacularly corrupt. Yet it seems to be impervious to correction. If it were truly done for the benefit of the principals, a very large number of the most highly paid financial workers in the country would be thrown out of jobs. This is not likely to happen.

But what is most distressing is not just that these people are earning such high levels of compensation, but that they are widely admired and even lionized for what they do and for the money they make, because it is not widely understood what they are actually doing. This needs to change. There is much talk about how many people lack a good financial education. That education should include frank and factual information about this industry.

Original Article

1 See “Alphas and the Choice of Rate of Return in Regressions”; Edhec-Risk Institute Research Insights, June 2014.