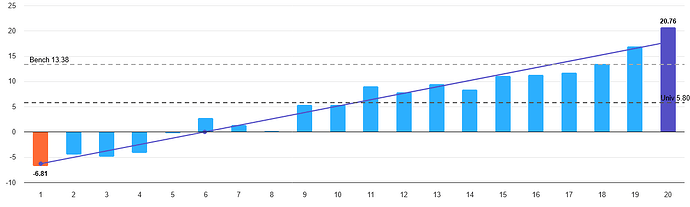

The accrual ratio that I’ve been using, to extremely positive effect in my backtests, is (NetIncBXorTTM-OperCashFlTTM)/AstTotTTM, with lower values being better. Using this formula heavily (about 10% or 12% of rank) instead of certain other “quality” measures improves my excess returns by up to 20% over any other system I’ve tried. But I don’t quite understand why. I suspect that it’s because it’s opening my portfolio up to growing companies with negative earnings rather than because it has any merit on its own—I’ve coupled it with a heavy emphasis on growth (earnings, operating income, revenue) and value in terms of price-to-sales. In terms of measuring quality, a reliance on ROE and ROCE will effectively eliminate companies with negative earnings, while the accrual ratio actually favors such companies.

Take two scenarios, for example. You have a company that’s declining. Your income is low, and prospects don’t look good. So you mine your inventory and receivables to generate additional cash. Your operating cash flow will be terrific, your net income will be low, and your accrual ratio will be negative–i.e. superb. But your company is in deep trouble. Or take the opposite situation. Your company is growing like crazy. You’re making a nice, tidy profit. And you’re investing your extra cash in additional inventory and accounts receivables, resulting in a negative net cash flow. So your accrual ratio is super high, an indication of earnings manipulation and danger ahead, but your company is going to do just fine.

Where am I going wrong here? I believe I’m making a fundamental mistake somewhere, but I don’t know what it is. I know that Sloan demonstrated that companies with low or negative accrual ratios really outperform those with high accrual ratios, but it doesn’t make sense to me given those two scenarios I just gave.