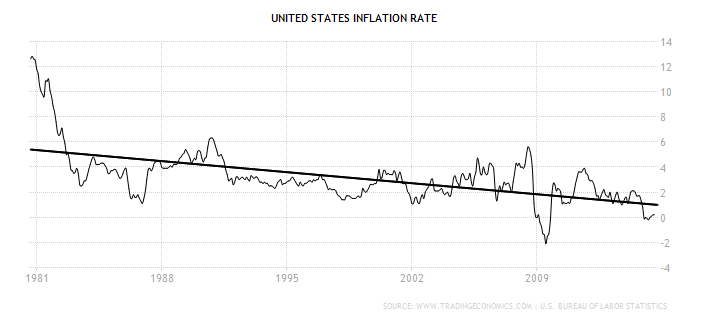

The fact that you brought 2006 into the discussion is reason enough for me to tell you to avoid TLT. The rate was 4.65% in 2006. Now it’s 2.55%. That’s a heck of a lot closer to zero than it was in 2006 so no matter what happens in terms of inflation or disinflation, there is only so much more room it can run.

Only so much more room is, of course, not the same as zero room. So if you had presented an argument for stability or flattening based on an analysis of the economy and solid reasons why you believe there will be enough additional news on the inflation/economic activity front to justify another nudge down, to 1% perhaps, or even to keep it at or near 2.55% and that you’d done the math and balanced the potential reward if you’re right versus the potential hit if you’re wrong, and assessed the relative probabilities of each, I’d say that if you were comfortable with your analysis, then by all means, go for TLT.

But that’s not what you’re doing. By pulling a completely irrelevant datapoint from 2006 into the discussion, I get a sense that you’re straining for ways to justify use of an asset that worked so wonderfully in simulations. That’s the kind of approach that can hurt you very badly. Please don’t do that to yourself.

And by the way, nobody has followed up on the point I made that TLT is even more dangerous than the 20-year treasury. The latter has a maturity date and every day between now and the, the bond will be priced with reference to that anchor of value. TL:T is an ETF that is obligated to roll its portfolio over such that the time to maturity id always 20 years. In other words, there is no maturity date.

That means TLT can’t trade like a 20-year bond. It will actually trade like a British Consul securities that are perpetual (Anyone here from the UK? Do they still have those?) This was a great feature when TLT and other fixed income funds debuted and got popular. It allowed the funds to outperform the bonds. But if rates rise, you don;t want to touch these funds with a ten foot pole since they’ll be much worse than the bonds.

If you want fixed income vehicles, consider target maturity ETFs, or surf around on Treasury Direct, through which it’s pretty easy for individuals to get direct ownership of treasury securities. At least that way, you have maturity dates. And, of course, bank CDs are fair game. We can’t really simulate it on p123. But simulation is a tool, it;snot the be all and end all of life. My recommendation is to simulate with cash as the hedge vehicle, and then do your fixed income things with short-data-history and not-to-testable target maturity ETFs, CDs or Treasury direct.