Yuval,

I agree that investors in the highest growth companies do poorly in public markets generally (unless they got in early and sell off to later stage investors), and I agree that it gets very, very hard to maintain these levels of growth and any valuation models assuming it will happen are likely in trouble.

An interesting example of the challenges of valuing a small, hi-growth company can be found here - in this discussion of the argument around Uber:

-

Uber isn’t worth $17B.

Uber Isn’t Worth $17 Billion | FiveThirtyEight

(see the attached spreadsheet on this - it’s a good reminder of very traditional valuation methods)

-

uber could be worth over $40B.

How to Miss By a Mile: An Alternative Look at Uber’s Potential Market Size - Above the CrowdAbove the Crowd | By Bill Gurley

(it’s a good thought exercise on selling / hyping a company and/or the challenges of valuing very hi-growth, ‘new business models.’)

This article raise interesting questions about how to value companies, but also points to the fact, that simply valuing a company based only on it’s 12 Month or 24 month growth rates is FRAUGHT with large conceptual issues. This is what I thought you were asking, and I was trying to help.

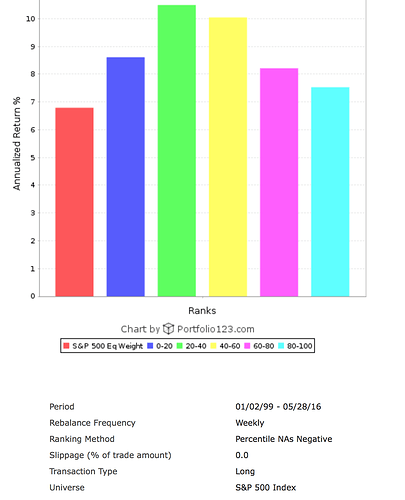

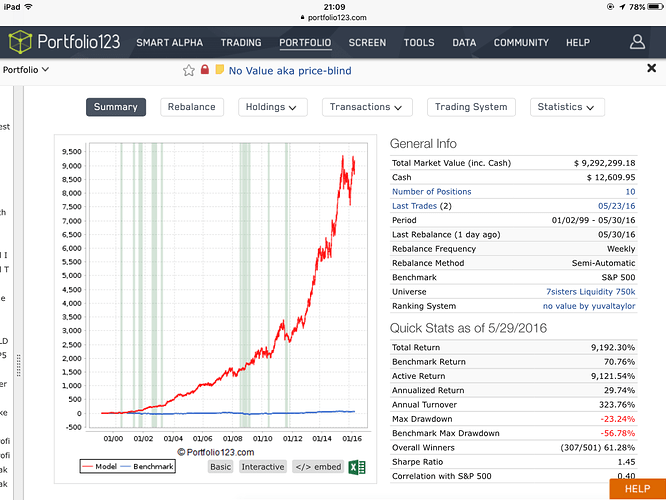

Your ranking system - unless you add some value component to it - feels largely like ‘pattern matching’ based on backtests and optimization. I am not against using those tools, but I believe that you are only making claims that exceedingly high growth is bad, because backtests show it’s bad in terms of stock market price movements in near and medium term. That’s pattern matching and nothing more. It’s the same as looking for patterns in price. You may then construct logical arguments (like the market overreacts and adds too much ‘growth premium’ to multiples), but it’s still pattern matching.

If you were to examine those companies that grew at 40% in a year and then looked at their total sales growth over the next 3 years, my bet is that it’s higher (that is raw sales and earnings growth is higher) than companies that grew at -5% the following year. But that doesn’t matter for an investor (the price movements of the stock do).

And if you were building a logical argument that companies that ‘grow too fast’ are bad, you would have ideal ranges of optimal growth for earnings, margins, etc. and penalize significant deviations and rises in these as well. The reason you don’t is likely that you built this through backtest based optimization (in one form or the other).

Best,

Tom

P.S. As far as me understanding revenue vs. ebit - I do:

I co-founded a company and grew it to over $200 Million in annual sales. I get the difference between revenue growth and earnings growth, and ours was much larger than 50% / year actually (around 100% / year over this time). In the past 3 years, I’ve also reviewed at least 200 business plans for 200 private companies with that level of growth over periods of many years seeking additional funding (seed or Series A) in the private markets. These are the companies that nearly all private tech investors seek out. If you are looking for small companies and using a growth model, it seems that you might want to copy what the best investors in the world in this space are doing - at least to start. But, that’s only if you have a similar holding period (a long time - like 8-12 years). If you have a shorter holding period, you don’t - but then you are using pattern matching - and should be looking at mathematical models for how to do that well, not looking for logical justifications for it.

P.S. #2 As far as Amazon:

Amazon was founded 22 years ago and is valued at $336 Billion or so. So, they’ve compounded value since founding at roughly 230% annualized per year (assuming they were worth $1 the day they incorporated). I don’t want to argue too much about this particular case, and I absolutely agree on is that hi-growth businesses and industries are typically much harder to value well - and the uncertanties are much higher as the time horizon grows.

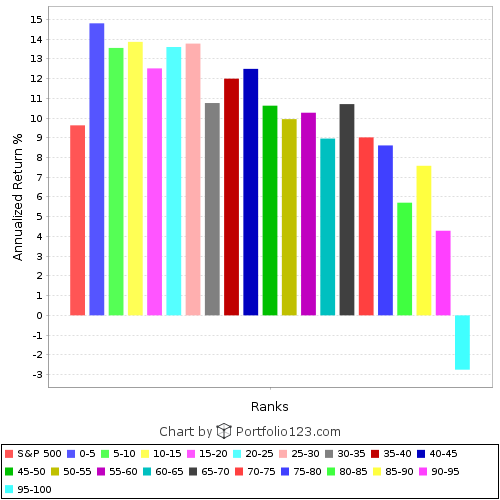

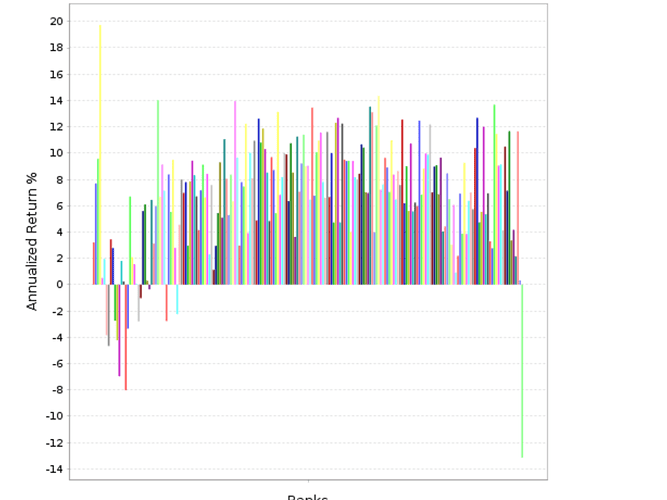

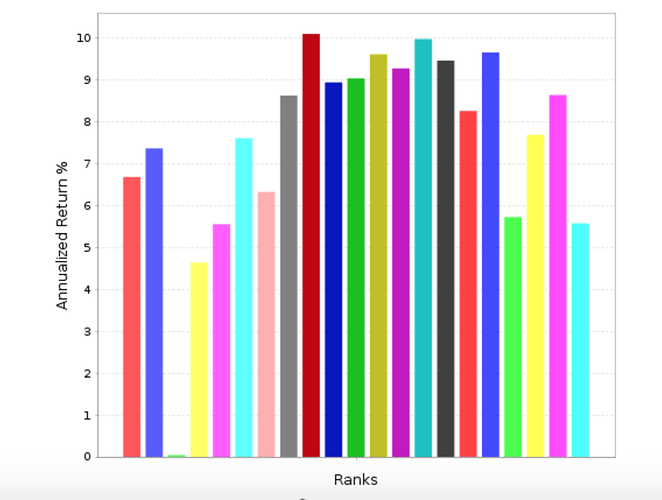

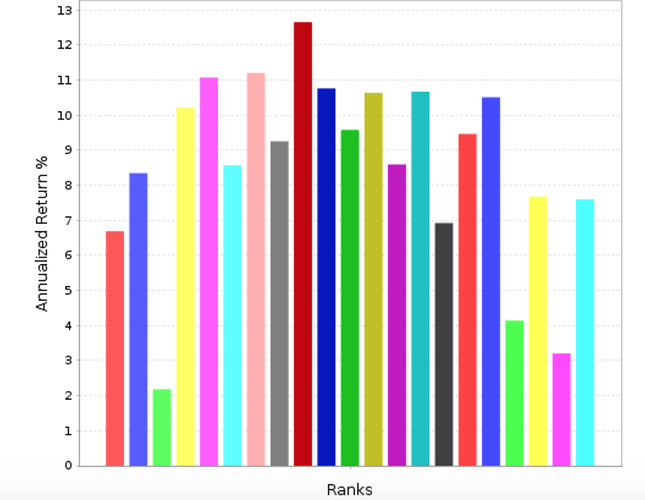

PS # 3. As far as companies that have grown sales more than 40% TTM, if hold them for 1 year - here’s the numbers from P123 (rolling test every month, 365 day hold) - they tend to do much better in the next year than average companies in up markets, and get punished more in down markets - but my point was none of this matters - and this is all saying nothing about their sales growth and business performance, just the stock market reaction to it:

GROWTH BENCH

Average 528.19 4.84% 4.15% 0.70% -95.77% 442.92% 61.26%

Up Markets 149 451.07 19.62% 13.62% 6.00% -94.00% 512.37% 67.42%

Down Markets 65 704.95 -29.05% -17.57% -11.48% -99.83% 283.72% 47.14%

This again, is pattern matching.

ubervaluation-Professor-NYU.xls (101 KB)